Ancient Egyptian Language and Literature: From the Old Kingdom to the New

Introduction

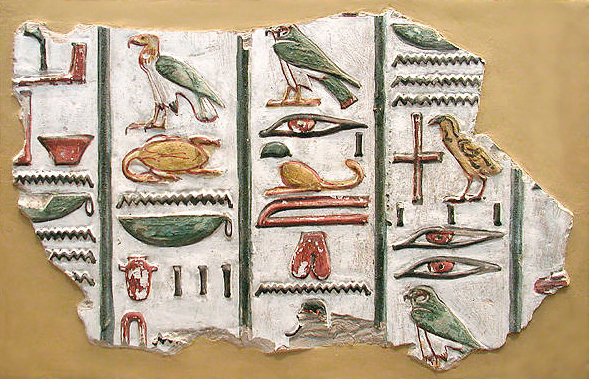

When you think of Ancient Egyptian as a language, you probably think of the famous hieroglyphs (such as those pictured left) drawn or engraved all over Egypt’s ancient tombs, but did you know that there was another, less formal writing system that the ancient Egyptians used for their everyday writing? Do you know how Egyptian hieroglyphs were first translated? Did you know that the ancient Egyptians were such prolific writers that they were the first to invent a paper-like material? Have you ever been curious to read some of their literature, but weren’t sure where to start?

Ancient Egypt has long been a fascination of mine, so come join me as I explore their beautiful language, their complex writing systems, and their large body of diverse literature. For a culture that became so famous for its well-preserved tombs, Egypt has also preserved thousands of years’ worth of the life of its people through its culture of meticulous record keeping.

The Ancient Egyptian Language

Ancient Egyptian is part of the Afro-Asiatic language family, which includes many languages from North and sub-Saharan Africa as well as the Middle East. This family includes Hebrew and Arabic, the latter of which blended with a form of ancient Egyptian after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 AD/CE, creating the dialect known as Egyptian Arabic that is spoken in Egypt today.

Hieroglyphs

Back during the Old Kingdom (c. 2650-2150 BC/BCE), the ancient Egyptian language was in its Old Egyptian phase, which took the place of the Archaic phase from Egypt’s early history. During the Old phase, a hieroglyphic script was developed, which combined ideographic (a symbol representing an idea), logographic (a symbol representing a word), syllabic (a symbol representing a syllable), and alphabetic (a symbol representing a sound) symbols to achieve a uniquely artistic representation of the language. To learn more about how to read Egyptian hieroglyphs, check out the video below from The British Museum on YouTube:

Hieratic

However, this hieroglyphic script was mainly used for royal inscriptions and important religious texts. In other words, it was used to make grand statements look especially impressive. Would the royal tombs look as artistically magnificent if all the inscriptions used an alphabetic script? Probably not. But if you were a regular person trying to keep records for your business, write a letter to someone, or relate your day’s experiences in your diary, you wouldn’t want to draw all those complicated little pictures for each sound or syllable. That’s where the hieratic script came in. Hieratic script was cursive, meaning that symbols could be joined together for one smooth motion by a pen on papyrus, a paper-like material the ancient Egyptians made from the pulp of the papyrus plant. You can learn more about the hieratic script below in a fun video from Hoison Poison on YouTube:

Demotic

The Middle Kingdom (c. 2050-1780 BC/BCE) saw the Middle phase of ancient Egyptian, and the New Kingdom (c. 1750-1070 BC/BCE) the Late phase, though Middle Egyptian was still used as a literary language for centuries. By 700 BC/BCE, both the language and the script underwent further changes, becoming Demotic Egyptian. Interestingly, while hieroglyphs can be read either left to right or right to left, hieratic and demotic scripts must be read from right to left.

Coptic

The final stage of the ancient Egyptian language, from sometime around 200 AD/CE until the Muslim conquest brought Arabic to the country, was Coptic. Since this was the language of Egypt at the time that Christianity arrived in the region, it remains the liturgical language of Coptic Christians even to this day. It is written with a combination of letters from the Greek and Demotic alphabets.

Translation

The wealth of literature written in ancient Egyptian was a mystery to the world for centuries after hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts fell into disuse. Then, in 1799 AD/CE, invading French soldiers discovered a stone tablet near Rosetta, or Rashid, a port city at the Nile Delta. The tablet contained the same inscription written in hieroglyphs, in demotic script, and in ancient Greek. Since scholars already knew how to read the latter, it only took a few years of devoted research for philologists (most notably Jean-François Champollion) to decipher the Egyptian scripts and, from there, apply what they had learned to other ancient Egyptian texts.

Ancient Egyptian Literature

Ancient Egyptian literature is a diverse body of works spanning thousands of years, and archaeologists are still finding new examples to this day. The ancient Egyptians were meticulous record keepers, poets, letter-writers, hymnists, diarists, and even autobiographers. Scribes (professional transcribers) were considered a privileged class in ancient Egyptian society, and, while perhaps only a small percentage of the population could read and write, there seemed to be a literate person assigned to record most aspects of Egyptian life.

As for popular stories, The Tale of Sinuhe and The Eloquent Peasant were widely enjoyed and still survive for us to read today. Of course, a lot of the Egyptian writings that have been discovered and translated tend to be those preserved in tombs, pyramids, and temples, so ritual texts like The Egyptian Book of the Dead are readily available to us. The Book of the Dead is a collection of spells that was left in a deceased person’s coffin or burial chamber to help them on their journey into the afterlife, and it appeared to go through many changes over the centuries of its popular use. Each one was probably tailored to the needs of each deceased person, since no two copies contain the same arrangement of spells.

The Papyrus of Ani

The Papyrus of Ani is the most notable version of The Book of the Dead that survives today. It was found in the Theban tomb of a scribe named Ani, who died around 1250 BC/BCE. As despicable as this will sound to a post-colonial mindset, the papyrus was stolen from Egyptian authorities by English philologist E. A. Wallis Budge, who was richly rewarded by the British Museum for it and went on to translate it into English. I thought it was important to acknowledge that unsavory aspect of our collective knowledge of ancient Egypt – I love to learn about the ancient world, but that doesn’t mean I approve of the methods that were used to present us with that ability. Repatriation matters!

I hope you enjoyed this look at ancient Egyptian language and literature. It’s a subject I can never get tired of talking about! I hope you’ll join me next week for an analysis of The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Leave a Reply