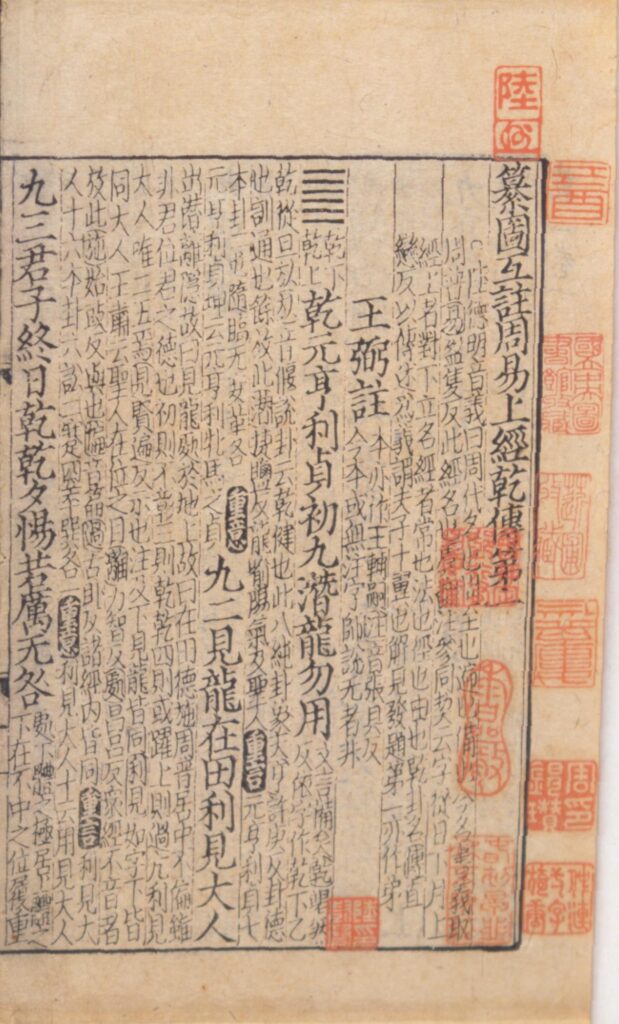

(image: Title page of the I Ching, c. 1100 AD/CE – http://catalog.digitalarchives.tw/item/00/08/73/99.html, Public Domain)

As I mentioned previously in my post about the Old Chinese language, the earliest examples of written Chinese come from oracle bones, pieces of ox scapula or turtle shell that were used in divination rituals and began to include written language as far back as 1250 BC/BCE. These oracle bones are the basis for the I Ching, which started out as a divination manual somewhere between 1000-750 BC/BCE.

The book is organized as a list of 64 hexagrams, which are patterns of 6 horizontal lines stacked on top of each other. Within each hexagram, the lines are either solid or split in the middle (follow this link for a table of the 64 hexagram variations on Wikipedia), and these line-by-line differences are considered to have meaning. Originally, an unbroken line (yang) on an oracle bone would indicate a “yes” in response to the diviner’s question, while a broken line (yin) would indicate “no” (Wilhelm and Baynes, p. xlix). Over time, it is believed that the mythical emperor Fu Hsi developed the 64 hexagrams (p. lviii), King Wen of the Zhou dynasty (1113-1056 BC/BCE) organized them into pairs of yin and yang inversions known as the King Wen sequence (p. lix), and King Wen’s son, the Duke of Zhou, wrote text to explain each one (p. lix), turning this method of divination into “a book of wisdom” (p. liii). Eventually, the philosopher Confucius (c. 551-479 BC/BCE) edited and added commentary to the original I Ching, and that is the version that has endured through time to be enjoyed by us today (p. lix).

As ancient as the I Ching is, there is still a lot of wisdom to be gleaned from its pages. This text has influenced the teachings of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, wisdom-based belief systems that are still practiced widely today, but anyone can open the I Ching and learn something profound about human nature, social order, and how to live a good and meaningful life (the life of the “superior man” or the “gentleman,” as the seeker of self-improvement is called in Chinese philosophy). As an example of what the I Ching has to offer, here are a couple of hexagram verses and their commentary that stood out the most to me:

Clouds rise up to heaven:

The image of WAITING.

Thus the superior man eats and drinks,

Is joyous and of good cheer.

When clouds rise in the sky, it is a sign that it will rain. There is nothing to do but wait until the rain falls. It is the same in life when destiny is at work. We should not worry and seek to shape the future by interfering in things before the time is ripe. We should quietly fortify the body with food and drink and the mind with gladness and good cheer. Fate comes when it will, and thus we are ready. (p. 25)

If one does not count on the harvest while plowing,

Nor on the use of the ground while clearing it,

It furthers one to undertake something.

We should do every task for its own sake as time and place demand and not with an eye to the result. Then each task turns out well, and anything we undertake succeeds. (p. 102)

I certainly plan to take those words of wisdom to heart and do my best to live by them. Have you read the I Ching? What are some of its wise words that have stirred your soul? I would love to hear from you in the comments below. And please join me next in reading the Tao Te Ching, which I will be posting about next week.

Note: If you’re in the US and are interested in getting your hands on the I Ching, please consider using this affiliate link to my Bookshop.org shop, where any purchase you make will earn a small commission both for me and for the local independent bookstore of your choice. The exact edition I read from is sold right here. Thanks for your support!

Source used:

The I Ching. Translated by Richard Wilhelm and Cary F. Baynes. Princeton University Press, 1967.