Goodreads description: When Elise and her boyfriend, Tom, set off for Minnesota, all she knows about harvesting sugar beets (Beta vulgaris) is that her paycheck will cover a few months’ rent on their Brooklyn apartment. She’ll try anything to escape the incessant debt collection calls—and chronic anxieties about her body and her relationship. But as the grueling graveyard shifts set in, Elise notices strange threatening texts, a mysterious rash, a string of disappearances from the workers’ campsite, and snatches of a hypnotic voice coming from the beet pile itself.

As crewmembers vanish, Elise obsesses over Tom’s closeness with their charismatic coworker Cee and falls back on self-destructive patterns of disordered eating and dissociation. Against the horrors of her uncertain future, is the siren song of the beet pile almost . . . appealing? Biting and eerie, Beta Vulgaris harnesses an audacious premise to undermine straightforward narratives of class, trauma, consumption, and redemption.

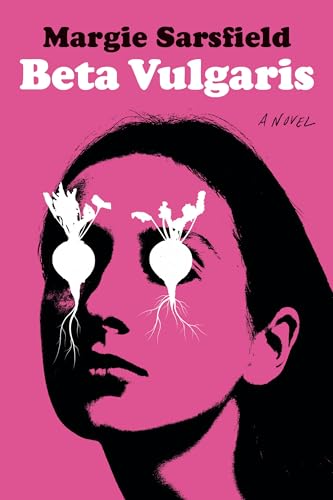

My review: I love beets. LOVE. We grow them in our garden, cook them, and freeze them, so I eat a couple of slices almost every day. You could say that a fair amount of my body mass is literally made of beets. LOVE them. I also love psychological horror and themes of metamorphosis. So when I saw a new horror release about a woman who hears sugar beets speaking to her and maybe sort of kind of starts becoming one, I jumped at the chance to read it. Not to mention the (intentional?) similarities in the cover design with a famous cover design for Mona Awad’s Bunny, the satirical horror novel that was my favourite read of 2024. I was excited!

I’m not exactly disappointed, but I’m not exactly NOT disappointed. This isn’t so much an anthropomorphized-vegetables story as it is the story of a troubled young woman slowly descending into madness. Or is it?

“The beets can only hurt you if you listen to them” is a vanishing sign Elise thinks she sees when she first arrives at the beet-processing facility, a literal sign that something is off about this place long before Elise’s mental illness starts to spiral out of control. From that point on, there’s a slight unsettling feeling that creeps into the narrative and slowly – very slowly – starts to build. Make no mistake, this is a slow-burn thriller with plenty of spine-tingles but very little adrenaline. The story even drags in the middle for a while, with Elise’s paranoid insecurities playing on repeat until you start to feel like it’ll never stop. However, that might be intentional – a tortured mind like Elise’s does get trapped in never-ending cycles of self-hate and paranoia, especially when an eating disorder adds malnourishment to the equation. The annoying repetitiveness of Elise’s thoughts starts to drive the reader crazy while Elise herself is spiraling, effectively taking us along for the ride while we question whether the beet-voices are real or just the manifestations of a psychotic break, whether the people around her are leaving the camp of their own free will or dying somehow without being reported, and whether Elise will ever just EAT SOMETHING and start thinking rationally again.

But just when I thought I was starting to dislike this book, I realized there’s clever allegory here. For one thing, the title Beta Vulgaris is the Latin name for the beet family, but on another level it speaks to the vulgarity of the thoughts that start to enter Elise’s head, as well as her feeling of being a beta – a submissive, passive person who feels insecure beside the alpha personalities around her. Elise also relates to the beets on a deep, personal level. The opening chapter of the novel describes the life and, especially, the death of a beet that is abused and exploited for the sugar that can be extracted from it. Elise, with her insecurities, her intense need to be loved, and her crippling eating disorder, feels a connection to these beings that are drained of their life and substance for the empty sweetness of sugar. Sugar beets are loved by everyone, like Elise wants to be, but only for what can be extracted out of them. Outside of their sweet taste, the beets are unappreciated and discarded, just like Elise.

Overall, while this novel has its flaws and leaves some questions unanswered (and while it might suffer from potential comparisons to Bunny, which it has very little in common with), it’s one that I’ll be thinking about and dissecting for more allegory for a long time. Margie Sarsfield is certainly a writer I will be keeping an eye on. This was an impressive debut.

(If you’re in the US and would like to purchase this book, please consider supporting both myself and your local bookstore by using this affiliate link to bookshop.org (which will open in a new tab). I will earn a commission on any purchase you make through this link, and so will your local bookstore. Thank you!)